Joe Tyson, a talented blacksmith of Carthage, North Carolina

- Feb 5

- 6 min read

Early in 2025, while picking an old junk store for axes, I came across a bundle of one of my favorite “non-axe” tools: turpentine hacks. These nifty little curved blades were an integral part of the naval stores production industry, and were quite often produced by blacksmiths who also crafted turpentine and boxing axes, so they tend to follow me home. Much like axes, sometimes these tools are stamped with a maker’s name, so tracking their history is occasionally possible. This bundle of hacks had 3 marked items, the one of which this post is about, was stamped “J. Tyson” over “Carthage, NC”. I drive through Carthage regularly (Carthage Farm Supply has locally made axe handles), so I was instantly interested in seeing where this little tool had originated.

If you’re from Carthage, noting the name Tyson associated with the town is relatively unsurprising. If you happen to be passing through the little town of around 3,000 citizens, you’ll likely note the mural dedicated to the “Tyson and Jones Buggy Company”, and may even notice the “Buggy Factory” building that was recently used by Southern Pines Brewing Company as a pub house. The Tyson of the buggy company was Thomas Bethune Tyson, the son of John Tyson, but neither was the “J. Tyson” listed on the hack. John Tyson had been a wealthy planter of the Carthage area who had also owned saw and grist mills.His son, Thomas B. Tyson, moved from the family plantation into Carthage in 1841, determined to be a businessman. There he started a mercantile business that was relatively successful, later leading to a partnership in the buggy making business of “Tyson and Kelly”, later reorganized as “Tyson, Kelly, and Company”, and then, around 1873, “Tyson and Jones”. The buggy factory was for many years they leading industry in Carthage, and was what the town was locally known for quite some time.

“J. Tyson” of my antiquated hack was associated with Thomas B. Tyson and did work at the buggy factory. However, he was not related to Thomas Bethune Tyson, at least by blood, and was simply known as “Joe” until the 1860s. The “J. Tyson” in question had been born a slave around 1841, and had been the “property” of the Tyson family. Though information on Joe’s father is scarce, his mother was noted as “Aunt Jennie”, an older woman who was reported to have been the nursemaid of Thomas B. Tyson. At a young age, Joe had been placed in the buggy factory to work, and it was there where he learned the art of blacksmithing.

Newspaper articles about Joe later on in life note that he had been born at “the Binneywood place”, the Tyson family home in the area that Edwin Binney, co-founder of Crayola Crayons, would one day have a summer home. At the time, Joe’s mother had been owned by John Tyson, and it would seem that Joe was raised in that location, though by the 1860 slave census, the majority of John’s slaves were listed under Thomas’s name on the separate slave census for the town of Carthage rather than the surrounding areas in Moore County. The next year, Joe married Eliza, a slave owned by the local physician, Dr. Hector Turner. 2 years later, in 1863, the same year that President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring all enslaved men and women in the United State free, the couple saw the birth of their first (surviving) child, Hannah Jane.

After the end of the American Civil War, Joe and Eliza were listed in records and newspaper articles under the surname “Tyson”, taking on last name of a former owner as was relatively common. The 1870 Federal Census notes “Joseph Tyson” as a 28 year old blacksmith in Carthage. Newspaper reports mention Joe working at the Tyson, Kelly, & Company buggy factory, and the names listed around his on the census include many men noted as blacksmiths, saddle makers, and leather workers, all occupations found in the carriage and buggy manufacturing industry. Eliza is listed occupationally as “Working in Shop”, indicating that she likely worked in the same facility as Joe.

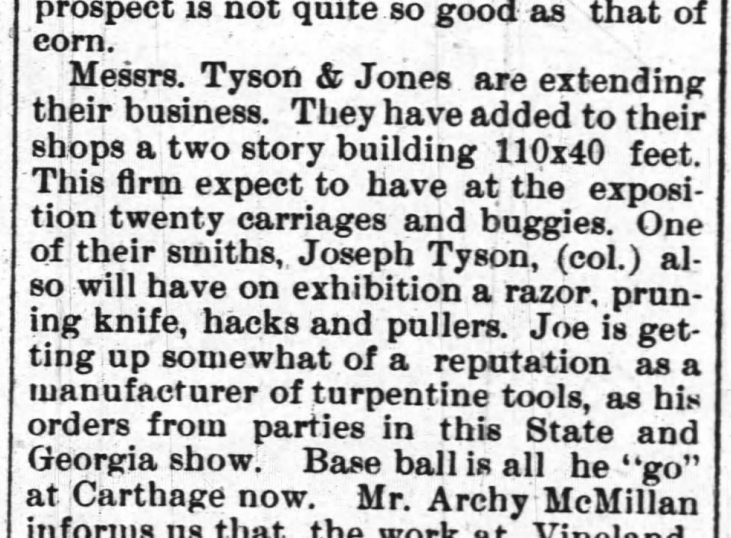

1870 also saw the start of a long list of accolades that indicate that Joe was not only growing in his profession, but was also excelling in it. Reports from the 1870 Cumberland Agricultural Fair, held November 23rd through 25th that year, mention Joe as winning the premium for saddlery, with his entry being a “very handsome silver plated harness”. His interest in metal work seems apparent, as by the 1880s, he began to be noted more in more for his work, especially when it came to bladed tools. Two groups of items stood out when it came to media mentions of Joe’s work: turpentine harvesting tools and razors.

During the 1880s, the naval stores industry was booming in North Carolina. The need for tar, rosin, and turpentine, all still considered “naval stores” due to their use in the naval industry, was still high, and the state had one of the highest populations of Pines in the “developed” portion of the U.S. Pine sap was the natural resource used to make these products, and the industry collecting it was responsible for a large portion of North Carolina’s economic output. To collect sap from Pines, a number of tools were used, including specialized axes and other bladed tools. Some of these tools were known as “hacks” and “pullers”. These bladed tools, made of iron and generally attached to a wooden pole, were used to scrape and gouge the surface of a Pine, allowing the sap to flow out and be collected. Though numerous northern companies produced these hacks and pullers for sale to the southern states, at the time, most of the tools of this sort were made by local blacksmiths of varying skill levels. This variance, along with a variety of grades of iron, led to widely varying degrees of quality in the tools, which led to reputations amongst the makers. Per local newspaper articles in the 1880s, Joseph Tyson was held in high regards when it came to his hacks and pullers. So much, in fact, that he was noted as gaining contracts for his tools from as far away as Louisianna.

The razors produced by Joe were described as of the finest quality, with hollow ground blades, metal handles, and inlays of silver. They were frequently noted as a source of pride to both he and the local community. In 1884, when the state held an Exposition to celebrate the 300th Anniversary of the Roanoke Voyages of Sir Walter Raleigh, numerous newspapers noted Joes razors as being displayed. He was also noted as sending his razors as gifts to a number of Presidents, including Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt. According to his obituary, prior to sending a handmade razor to Roosevelt, Joe visited a local barber inquiring as to which local had the coarsest beard. Once that man was identified, Joe had the man test the razor, and it was said that the coarse haired man noted it was the smoothest shave he had ever had. According to the article, Joe later received a personal letter of thanks from the sitting President.

The quality of Joe’s products (which also included locks and fruit pruners, along with hacks, pullers, and razors) led to both a steadfast reputation as well as what would seem a decent living. Articles in the local papers note him as having continued orders for his products locally and in Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana. He was noted as having a home with a separate smokehouse for meats ad a sizable stable. Adjacent to his home was his small blacksmith shop. His success was great enough to incur a legend that he had hidden a sizable sum somewhere on his property, leading to vandals digging holes and removing foundation stones while he was away. He fathered 11 children, at least 7 of whom lived to adult age. Though he was noted as becoming “somewhat miserly” after the death of his wife in 1903, county expense records note that he persisted in his work and also did metal work for the city, including repair work on the local jail.

Joe continued his life in Carthage through from before the American Civil War until after the first World War, and into the times known as the “Roaring 20s”. He saw the death of his mother, who lived to 106 years of age in 1894. He watched as his former owner was buried not far from his own home, in 1896. He witness the last buggy manufacturer at and delivered from the Tyson and Jones Buggy Factory in 1925. On April 26th of 1927, Joe Tyson passed away surrounded by family members. His death certificate notes that he was laid to rest by friends, with no undertaker noted. He was buried at the “cemetery of the colored presbyterian church”, now known as the graveyard of John Hall Presbyterian Church. If there was a headstone at his grave, it is no longer visible. However, Joe’s legacy lives on in hardened steel and iron of such quality that, when sharpened, is just usable today as it was 100 years ago, and the stamp of “J. Tyson Carthage NC”.

Comments