The Mack Axe Co., Winchester, E.C. Simmons, and the "Keen Kutter" Line of Axes

- Jul 13, 2025

- 6 min read

The history of the Mack Axe Company is often littered with confusion, especially in its final years, due to corporate switch ups and subsidiary listings from the conglomeration that was the short lived Winchester-Simmons Company. The buildings that would become the Mack Axe Company began as the factory of Joseph Graff and Company. Originally operating out of Pittsburgh as Newmeyer, Graff, and Company, and then Joseph Graff and Co., Graff left the bigger city and found a nice spot along the Beaver River at Beaver Falls around 1871. In 1879, Hubbard and Company would buy the factory as they reorganized the assets they had in the saw, shovel, and axe world, choosing to manufacture their edge tools there in Beaver Falls. In an odd tangent, a young William J. Sager would work at Beaver Falls around 1880 before moving on to Brookville, then Ridgway, and finally Warren. In 1889, the Hubbard family and their axe based assets, including the factory at Beaver Falls, would become an initial portion of the American Axe and Tool Company, and he Beaver Falls facility was renamed “American Axe and Tool Factory #1”.

Another initial member of the American Axe and Tool Company was Fred T. Powell, owner of the Jamestown Axe Company at Jamestown, New York. At the time, one of his chief managers was a gentleman by the name of John Mack. Mack was a native of Jamestown who had risen through the layer of manufacturing to become a leader at the factory. In 1900, as the A.A. & T. Co. was consolidating its factories in order to utilize their new facility at Glassport, Pennsylvania, the Jamestown Axe Company was closed, its machinery moved to Glassport. Due to the reorganization as well as Mack’s technical knowhow, the veteran axe maker was sent to Beaver Falls to work as the work’s superintendent. Due to a number of factors, Factory #1 was one of the last of the American Axe and Tool Company’s factories to be consolidated, and lasted until around 1911. Though it had suffered a fire that partially destroyed it in 1909, the works had crippled along, but couldn’t avoid cancelation forever. In 1911, as William C. Kelly and his Kelly Axe Manufacturing Company were slowly buying up the majority stock in the A.A. & T. Co., they also bought out the floundering factory at Beaver Falls. The move was a consolidative strike aimed at “trimming fat”, much like the closing of the works at East Douglas, and the facility was immediately sold to recuperate the purchase cost. The buyer was none other than John Mack and his family.

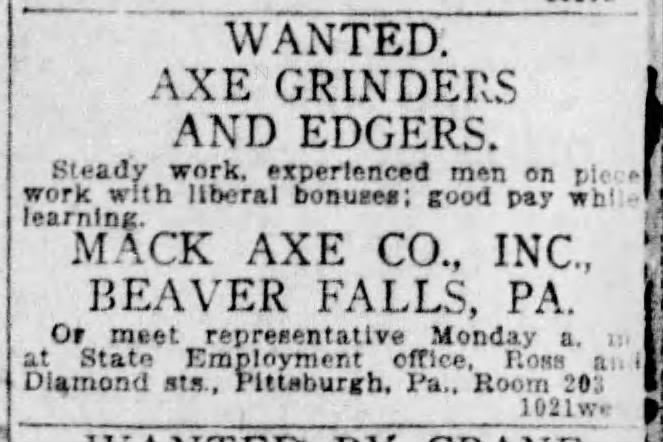

Toward the end of 1912, trade journals and local media began to publicize that Beaver Falls would soon see a new edge tool factory under the name “Beaver Falls Axe and Tool Company”. From the start, there was no hiding that John Mack would be the manager, though there seemed to be some reluctance to noting him as the owner. The initial reports noted that the factory would be up and running by January 1st of 1913, but, like happens most of the time, there were some delays, with the factory opening in the spring of 1913. By the end of the year “The Mack Axe Works” at Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, were advertising products in the United States and Canada. Their initial lines were the Maxax, the Feller, the Chipper, the Beaver, the “66”, and the Ottawa Chief. All 6 lines were advertised as holding a sharp edge longer than any other axes made. Though a bit ambiguous in ownership at first, by the summer of 1914, the “Mack Axe Company” had been incorporated with a capital stock of $60,000. The initial board of directors was composed of John Mack, Frank Mack, Julia M. Mack, and Mary Mack. It’s quite interesting to note that 2 of the 4 initial directors were the family’s primary female members (Mary was John’s wife, and Julia his oldest daughter). The factory was noted as employing up to 125 men, though scant labor records note the average to be less than 100.

It’s important to remember that during the time the Mack’s owned the company, there’s little evidence to show that they manufactured axes with etches or bevels as standard lines. Known examples of Mack Axe Company tools generally have faint stamps, and most were likely paper label versions of the lines named above. Comparatively speaking, the works were likely quite simple. Whatever the complexity, the company faired well and continued production through until the roaring 20s.

In June of 1920, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, looking to grow its assets and diversify its product lines, bought the Mack Axe Company. The axe manufacturing concern was reportedly one of nine minor manufacturing companies acquired during the firearms company’s growth push, though a few were immediately consolidated. Many authors mention that the goal of the purchases by Winchester was to move the equipment from those new assets to the home location at New Haven, Connecticut, though this would be at great cost and loss of capital, as it there would have been obviously cheaper alternatives to this. Publicly, Winchester noted the Mack Axe Company as a subsidiary. The 1921 Sanborn Fire Insurance Company maps for Beaver Falls note the factory there as “Sanborn Maps noted “Mack Axe Co Inc, Winchester Repeating Arms Co. Owners”. That same year, John Mack, who had been noted as a chief engineer and operations manager after Winchester bought the company, died. His position was taken by Herbert M. Wilcox who was also the manager of “Barney and Berry, Inc.” another subsidiary that Winchester had purchased in its growth push. Barney and Berry were primarily makers or roller and ice skates, but were also noted makers of small metal tools such as hatchets and shovels.

As Winchester grew its manufacturing capabilities, it eyed its options for distribution and sales, and in August of 1922, it officially merged with the E.C. Simmons Hardware Company. At the time, this was one of the largest mergers of consumer goods and sales that had occurred in the U.S., and the growing pains were obvious. At the time of the merger, Winchester’s physical assets included their firearm manufacturing facilities, their retail store at Boston, Barney and Berry, the Walden Knife Company, the Mound City Paint and Color Company, the Roanoke Spoke and Handle Company, and the Mack Axe Company. E.C. Simmons provided a slew of retail and wholesale locations and warehouses, though they held no manufacturing facilities. The new conglomerate was known as the Winchester-Simmons Company.

Almost immediately the company began to lose money. Though the new company pushed expansion in 1923, by 1924 the Winchester-Simmons Company was showing undeniable losses. To compensate, they closed hardware stores at some of their largest locations, including Boston, Springfield, Providence, New Haven, Troy, and New York. The publicized loss of capital was noted as $2,350,152. At that point, the actual growth stopped, and the company was seemingly in panic mode. Though they would purchase a few assets at strategic points later on, most of their damage control was done by dumping assets. One of those assets was the Mack Axe Company. 1925 was the last year that the axe factory was noted as a functioning business in the Beaver Falls Directory. Men and women noted in that directory as employees of the company were noted with different employers after that time, and the listing of the company in the business portion of the text disappeared. The Mack Axe Company, even as a subsidiary of a larger business, was no more.

In 1927, as the Winchester-Simmons Company continued to press forward, a large catalog of goods was published by the company. In it, there were thousands of products for household and business use, including a large number of axes and hatchets, including E.C. Simmon’s flagship brand, the “Keen Kutter”. For Keen Kutter variants along, the company offered dozens of combinations of weights, patterns, and handle sizes, many with heads acid etched with a “Keen Kutter” logo (the standard wedge shaped logo, the No. 5 logo, and others). There were numerous bevel types available for “Keen Kutter” etched heads as well, including the standard “Kelly Bevel” and the “Phantom Bevel” of the American Axe and Tool Company. Along with all of these upper end Keen Kutter variants, lower end in house brands, such as the Oak Leaf, the Mesquite, and the Bay State lines were available with paper labels. As side offerings, there were a list of Kelly lines, such as the Kelly Perfect, the Kelly Standard, and the Falls City, available. D.R. Barton axes, Marbles, and Underhill offerings are also noted. Interestingly, no Winchester branded axes or hatchets are listed in the catalog. These axes would have been distributed by the numerous Winchester-Simmons Wholesale stores throughout the U.S. and would have been sold in the tens of thousands.

By 1929, the Winchester-Simmons Company had run out of options for showing profitability, and the company began the process of rebranding. In May, the company chose a new name, the “Mercantile Securities Company”. 5 months later, the stock market crashed, signaling the start of the Great Depression. Early the next year, Winchester finally closed the last non-firearm manufacturing facilities it owned, Barney and Berry, the Eagle Pocket Knife Company, and the Whirldry Corporation. The following year,1931, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company separated its assets from E.C. Simmons, undoing one of the largest mergers of the times. Despite the reversal, the Mack Axe Company had been lost to the fray, and would not return.

Comments